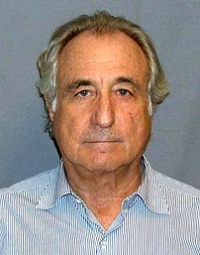

I was interested to read an in-depth account in New York magazine of swindler Bernie Madoff's experiences at the Federal prison in Butner, North Carolina. Here's a brief excerpt from a very long article.

[One] evening an inmate badgered Madoff about the victims of his $65 billion scheme, and kept at it. According to K. C. White, a bank robber and prison artist who escorted a sick friend that evening, Madoff stopped smiling and got angry. “F*** my victims,” he said, loud enough for other inmates to hear. “I carried them for twenty years, and now I’m doing 150 years.”For Bernie Madoff, living a lie had once been a full-time job, which carried with it a constant, nagging anxiety. “It was a nightmare for me,” he told investigators, using the word over and over, as if he were the real victim. “I wish they caught me six years ago, eight years ago,” he said in a little-noticed interview with them.

And so prison offered Madoff a measure of relief. Even his first stop, the hellhole of Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), where he was locked down 23 hours a day, was a kind of asylum. He no longer had to fear the knock on the door that would signal “the jig was up,” as he put it. And he no longer had to express what he didn’t feel. Bernie could be himself. Pollard’s former cellmate John Bowler recalls a conversation between Pollard and Madoff: “Bernie was telling a story about an old lady. She was bugging him for her money, so he said to her, ‘Here’s your money,’ and gave her a check. When she saw the amount she says, ‘That’s unbelievable,’ and she says, ‘Take it back.’ And urged her friends [to invest].”

Pollard thought that taking advantage of old ladies was “kind of f***ed up.”

“Well, that’s what I did,” Madoff said matter-of-factly.

“You are going to pay with God,” Pollard warned.

Madoff was unmoved. He was past apologizing. In prison, he crafted his own version of events. From MCC, Madoff explained the trap he was in. “People just kept throwing money at me,” Madoff related to a prison consultant who advised him on how to endure prison life. “Some guy wanted to invest, and if I said no, the guy said, ‘What, I’m not good enough?’ ” One day, Shannon Hay, a drug dealer who lived in the same unit in Butner as Madoff, asked about his crimes. “He told me his side. He took money off of people who were rich and greedy and wanted more,” says Hay, who was released in December. People, in other words, who deserved it.

There is, as it happens, honor among thieves, a fact that worked mostly to Madoff’s benefit. In the context of prison, he isn’t a cancer on society; he’s a success, admired for his vast accomplishments. “A hero,” wrote Robert Rosso, a lifer ... “He’s arguably the greatest con of all time.”

. . .

From the moment he alighted, he had “groupies,” according to several inmates. Prisoners trailed him as he took his exercise around the track. ... “They buttered him up,” one former inmate told me. “Everybody was trying to kiss his ass,” says Shawn Evans, who spent 28 months in Butner. They even clamored for his autograph.

And Madoff was usually more than happy to respond. “He enjoyed being a celebrity,” says Nancy Fineman, an attorney to whom Madoff granted an interview shortly after his arrival at Butner. (Fineman represents victims who are suing some of Madoff’s “aiders and abettors,” as she calls them.) Madoff seemed surprised and tickled by the lavish treatment, though he steadfastly refused to sign anything. Even in prison, he wasn’t going to dilute the brand. “He was sure they would sell it on eBay,” Fineman told me. “He still did have a big ego.”

Remarkably, that ego appears to have survived intact. H. David Kotz, the Security and Exchange Commission’s inspector general, investigated his agency’s failure to uncover Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, and Madoff volunteered to speak to him—he is, no doubt, the world’s expert on the subject. He quickly reminded Kotz of his stature — “I wrote a good portion of the rules when it comes to trading,” Madoff said. He insisted that he’d been “a good trader” with a solid strategy, explaining that he’d stumbled into trouble because of his success. Hedge funds — “just marketers,” he said with evident disgust — pushed cash on him. He overcommitted, got behind, and generated a few imaginary trades, figuring he’d make it up — and never did. Whatever his own missteps, Madoff saved his scorn for the SEC. He did impressions of its agents, leaning back with his hands behind his head just as one self-serious agent did — “a guy who comes on like he’s Columbo,” but who was “an idiot,” Madoff said, as recorded in the extraordinary exhibit 104, a twelve-page account of the interview that is part of Kotz’s report. Madoff is no ironist. His disdain for the SEC is professional, even if the agency’s incompetence saved his skin for years — all Columbo had to do was make one phone call. “[It’s] accounting 101,” Madoff told Kotz, still amazed.

Madoff’s ego was on display in prison, too. “Bernie walked around prison confident,” says ex-con Keith Mack, adding, with a trace of resentment, “he acted like he beat the world.” And to most inmates he had.

. . .

But however soft, prison is a hardship. And on his way to Butner, Madoff opened up to Herb Hoelter, the prison consultant known for helping ease celebrity prisoners onto their new paths—he’d previously worked with Martha Stewart.

“What do I do with my life now?” Madoff asked Hoelter.

That’s the existential challenge of prison, especially for someone with a life sentence. And there aren’t obvious answers. There’s little meaningful to do—nothing “aspirational,” as a tax evader who’d served time in Butner complained. Free will is limited. “You sleep and eat and s*** and shower when they tell you to,” a recent Butner releasee told me. Freedom, such as it is, is in the mind. “It’s your ability to think that’s not circumscribed,” explains Art Beeler, the warden until last year. But Madoff has never been an intellectual — he has the mentality of “an auto mechanic,” one hedge-fund manager told me. He keeps it simple, and it works. And so in prison, “Bernie adjusted better than I did,” says Hay, who slept a few doors down from Madoff. “He didn’t seem like he had any worry or stressed too much or had nerve or panic attacks, like I did. Going from an $8 million house”—his penthouse on East 64th Street—“to an eight-by-ten cell, I would feel smothered. Bernie never complained that I heard.”

. . .

Madoff threw himself into the prison-work world, applying for jobs as energetically as a new college grad. Madoff told Fineman that because of his age, he wasn’t obligated to work, but how else to fill the time? He’d always been industrious — keeping the con going was a continual hustle — and initially he’d hoped for a spot on the prison-landscaping crew. He proposed that he serve as the clerk in charge of budget. He had qualifications — he’d been chairman of NASDAQ. “Hell, no,” said the supervisor to Evans, laughing. “I do my own budget. I know what he did on the outside.” In an August 13 call-out sheet, which lists prisoners’ daily assignments, Madoff’s is maintenance. He gave out paint. Later, he was assigned to the cafeteria, where he walked around with a dustpan and broom, sweeping up dropped food for 14 cents an hour, the wage earned by new arrivals.

There's much more at the link.

One thing is clear: for all his Wall Street inside knowledge, for all his rich-and-famous lifestyle, Madoff's attitudes are much the same as those of any other prisoner. Working as a prison chaplain, I had the opportunity to observe such attitudes many times. It's the fault of the victims that they got taken; the criminal is a greater or lesser 'success' depending on how many people he's snookered out of how much money; and one's status in the prisoner hierarchy is basically a reflection of how much damage one's caused to society, and how much misery one's brought to others.

It's a strange, twisted world behind bars: and it looks like Bernie Madoff, for all his pretensions, fits right in there. I wonder how many other Wall Street mavens would do likewise? More than a few, I suspect . . . judging by their public personas, they appear to be as rapacious, greedy and self-centered as most of the criminals I've met.

Peter

No comments:

Post a Comment